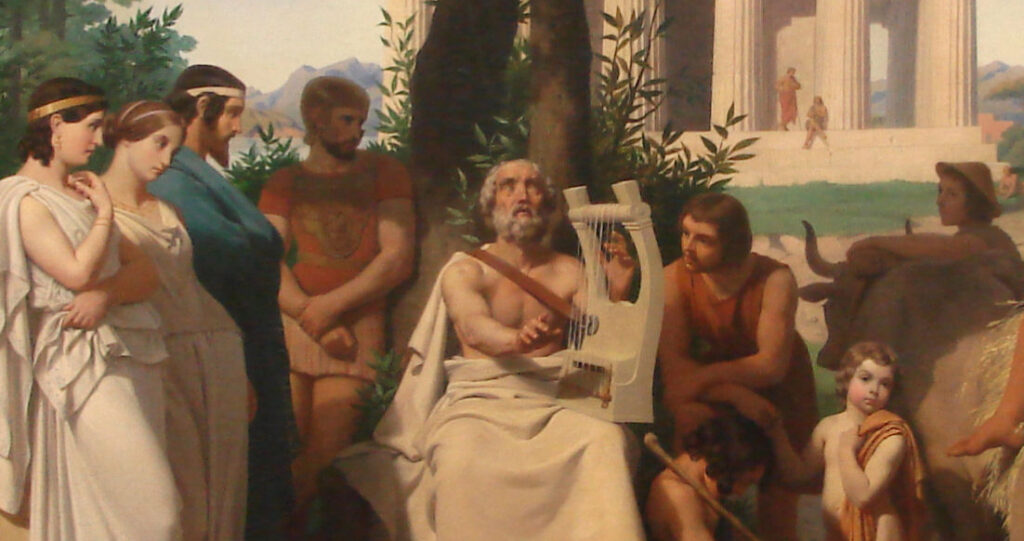

“Zeus set destiny upon us, so hereafter we would be the subject of songs for men who live in the future”

– Helen to Hector, Iliad Book VI – Homer

Hello! Here at Helicon HQ we’ve decided to share with you some of our tips and tricks from rehearsals. Whether you are an aspiring storytelling company like us, a theatre company who wants to hone your groups storytelling skills or just someone with a big presentation coming up at work, storytelling skills have been proven to help in all walks of life.

Indeed, a huge market for storytellers is the running of workshops for schools, businesses and communities, helping to improve public speaking, confidence and clarity, as well as enabling people to find their voices and share their experiences.

With this in mind, we want to share with you a couple of the games we regularly play during rehearsals to sharpen our story skills! Since our focus is Homeric stories, there are a couple here that are particularly suitable for an epic style, but can easily be adapted for other styles.

- Zip Zap Boing

Whilst not storytelling specific, this is a game well known to all amdram and student theatre groups. It’s our go-to warm up. We play this at the start of every rehearsal and it’s a great way to get everyone’s energy up and put them in the drama zone.

To Play:

- Stand in a circle.

- The first player claps their hands and says “Zip” at the same time, and points at a player next to them in the circle.

- The next player can continue to clap and “Zip” to the next player in the circle, or they can reject the “zip” by saying “boing”, and throwing their hands up in the air.

- If you “zip” someone and they “boing”, you must turn the “zip” in the other direction and pass it to the player next to you. If A, B, and C are stood next to each other in the circle, A zips to B, B zips to C but C uses a boing, B must then zip back to A and so on.

- There is a third option; you can “Zap” by clapping and pointing at someone across the circle rather than next to you.

- Build up the speed and after a few practice rounds, if a player gets something wrong they are eliminated.

- When only three players remain, Zaps can no longer be used, as there is no longer anyone across from you!

To find a winner:

- When two players remain, they stand back to back and perform a duel. The eliminated players choose a category (eg. Fruit: Apple, Banana, Orange etc). When they shout out things that are in that category, the players in the duel take a step forwards. When something not in that category is named, the players in the duel must turn around “shoot” the other player; the first to shout “bang” wins.

Useful rules to remember include:

- You cannot zip a zip.

- You cannot boing a boing

- You may zap after you’ve been zapped, but it must not be back to the person who zapped you.

- You reject a zip with a boing and the zip-er then carries on in the opposite direction.

This game is fantastic and easily adaptable. We added in new rules, like the rejection of a Zap using “Reflector” and a Fireball which is “rolled” in a direction around the circle, forcing players to jump over it, or ‘put it out’ by shouting “water bucket”.

In addition, we tend to change the words Zip, Zap and Boing to be appropriate for the play we’re currently working on. For example, for The Battle of Frogs and Mice:

Zip = Squeak

Zap = Ribbet

Boing = Mousetrap

Reflector = Snake!!

Fireball = Greek Fire

Water Bucket = Pond.

- The Simile Game

This game is ideal for more literary storytelling and epic styles, but it’s also great for getting that creativity flowing and exploring some heightened language. First, ensure your group know what a simile is, and its purpose in literature: to give your audience something recognisable to compare with what you’re describing to them, or sometimes (as in Homer) to build tension by slowing down the action at moments of heightened emotion.

To play:

Sit or stand in a circle. Someone begins with a simile; we like to use ones that we know will be useful later in rehearsal. For example, “he ran as fast as an arrow”. Players then take it in turns to come up with a simile for the same thing; in this case, “how fast he ran”. They can stick with “as fast as” or change it to another description of the running, depending on how creative and confident your group is. The more creative the better, with extra kudos won for subverting the original meaning. For example:

Player 1: Her fear was as sharp as a knife.

Player 2: Her fear was as sharp as a particularly tart crab apple.

Player 3: Her fear was as bitter as a miser, forced to give up his last penny.

Player 4: Her fear was as strong as the farmers biggest and most reliable ox.

Player 5: Her fear was as sharp as a blunted spoon, struggling to cut through the softest of meat (that is to say, it was not very sharp!)

When you feel a simile has run its course, it can be ended by saying “so was her fear”.

This is a great game for finding interesting ways to describe things, and some really fun and creative stuff comes out. It often becomes a bit of a competition with people audibly complimenting each other on particularly visceral or beautiful imagery. We often write down our favourites as they are crafted, and try to use them later in our stories.

- Colour and Advance

This is a game for honing your storyteller’s ability to manipulate the story they are telling and be in control of it. Colour means description, while Advance means you need to move the plot along without stopping to describe things.

To Play:

We play this game in a variety of ways. It can be done as a part of Directors Cut, or it can be applied to a story that a group or individual has already been preparing. You can just shout out “Colour!” and “Advance!” but we like to use a giant play, pause and fast forward sign, where play means tell the story as normal, pause means stop and describe (colour), without moving the action forward until play is shown, and fast forward means you need to hammer on through the action as fast as possible.

This game is also useful for directors if you feel that your storytellers are struggling to identify natural places to stop and describe the scene, or if you feel they get caught up in the world building to a point where an audience may become disengaged because nothing is really happening.

- Bodge it!

This game was created by our need to give our storytellers the confidence that they can fix a story even after something has gone wrong. After-all, how easy is it to get halfway through a joke and realised you’ve forgotten to set up the punchline?

To Play:

A storyteller tells a story from a series of storybones. They are the most fundamental plot points of a story; for example, the storybones for Cinderella would be:

- Cinderella lives with her stepmother and two evil stepsisters.

- One day she wants to go to a ball.

- Her family set her impossible tasks to complete before she may go.

- With some magical help, she completes the tasks, gets a dress and goes to the ball.

- The prince falls in love with her at the ball.

- She leaves in a hurry, leaving a shoe.

- The prince tries the shoe on everyone until he finds Cinderella

As you can see there are lots of details missing; the pumpkin carriage, the fairy godmother etc. But these are all the details a storyteller can change and embellish when making the story their own. You can prepare storybones in advance or agree them with your group as part of the set up for this game.

The storyteller begins to tell the story. You and the other players can interject at any point with a correction or problem. For example:

Storyteller: Cinderella now had a wonderful pumpkin carriage to go to the ball in!

Player: The pumpkin carriage is broken

Storyteller: Unfortunately, the carriage was broken. But Cinderella was a great horse-rider and, picking up her skirts, jumped on the back of one of the horses and rode to the ball!

Player: But she didn’t know where the castle was

Storyteller: The horse, however, didn’t come with a sat nav unlike the pumpkin carriage, so Cinderella did not arrive at the ball until many hours after it had begun. They had spent at least 2 hours wondering around the forest, until they heard the music and rode towards it.

This game is particularly useful in group storytelling work, where another storyteller might change the plot so your planned ending is suddenly not feasible. Beware of making it too difficult though – don’t challenge EVERYTHING the storyteller says – just give them a few problems to work out!

- Directors Cut

This is probably our favourite storytelling game! It’s great for introducing storytelling into a setting or a group that haven’t tried it before and it’s also great for getting to know the people in your group and building a rapport.

To Play:

In groups, one person is nominated as Director. The director chooses the kind of story they want (funny/sad/serious/horror/fantasy etc) and someone to begin telling it. At any moment the director can shout out another player’s name, and that player must continue with the story. It’s particularly good to change the storyteller at moments of direct speech (“and then she said” *switch to next player*), moments of tension (“suddenly the door opened to reveal *switch to next player*) or when you feel someone is struggling to come up with the next bit of plot.

This game can have lots of add ins too. We like to play a version with Colour and Advance, a version where new characters are always introduced with an epithet, which must then be repeated by the whole group every time that person is mentioned, and versions set in the worlds of the story we are telling to help flesh it out in the minds of the storytellers.

So there were a couple of our favourite games to play! We’d love to know if you play them differently or if you enjoyed playing them. Tweet us a picture @HeliconStories !