It’s National Storytelling Week! The theme this year is ‘My Story – Your Story’, and that couldn’t be more true to what we were trying to achieve with our involvement in The Needles Art project alongside the Bodleian Library and Ornamental Embroidery. We wanted to share with you a little more about our stories, and how we came up with them, and hopefully inspire you to have a go at some yourselves!

The Needle’s Art Project

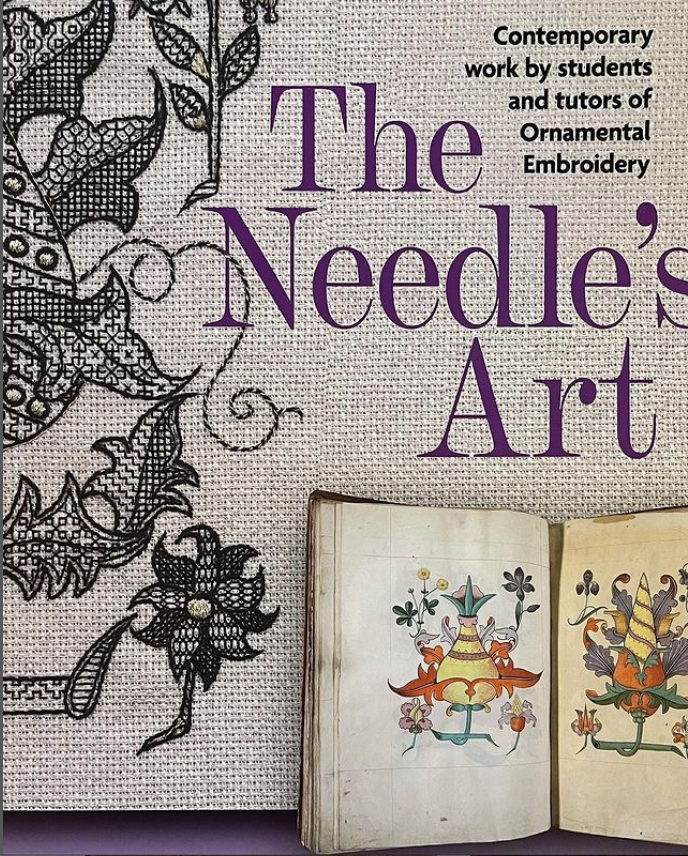

If you’ve seen our last blog post (or any of our social media feeds over the last couple months), you’ll know all about The Needle’s Art. But just in case, a quick bit of background. The Needle’s Art is an exhibition running at the Bodleian Library, showcasing contemporary embroidery by the students of Ornamental Embroidery, a company that specialises in the teaching and designing of historic needlework. All the work is inspired by a manuscript in the library’s collection: Ashmole 1504. It is a fascinating, if a little odd, Tudor illustrated manuscript; no one really knows its purpose. It’s not a written text with illustrations and marginalia but instead it’s filled with beautifully detailed scenes of flora, animals, heraldry patterns, household implements and alphabets. A popular school of thought is that it was a pattern book from which wealthy clients could select designs for their décor – furniture, hangings, all sorts.

The exhibition is only on until the 31st of January, so if you’re in Oxford make sure you pop into the Weston Library or Proscolium to check it out!

‘My Story – Your Story’

Now back to Storytelling and ‘My Story – Your Story’. To accompany the exhibition, we were tasked with creating six storytelling films; three short ones that could be used on social media and three longer ones exploring some themes in more detail (you can watch all our films here). We wanted to approach Ashmole 1504 for storytelling exactly as one would a pattern book. Just like the embroiderers of Ornamental Embroidery, we trawled the manuscript for interesting images, characters and settings, and used these as building blocks to create our stories – but you could do the same – explore the manuscript, choose your favourite illustrations and use to them to create your story (or perhaps a drawing or embroidery). To help give you an idea of how to do this, throughout National Storytelling Week, we’re going to go into detail on each story, sharing how we came up with it, which elements of Ashmole 1504 we incorporated, what contemporary sources we drew upon, and how the stories came together. First, let’s jump in with our overall process for the films and stories.

Our Process

For the short films, we needed to show the flavour of the manuscript in less than 60 seconds, and so – because we’re huge word nerds – we decided the best way was to share the etymologies behind some of the flora and fauna depicted. That’s how we ended up with Foxgloves, Belladonna and Swan Song. Given the time constraints, we decided to entirely script these rather than follow our usual Helicon improvisational method. The videos ended up sharing as much with poetry as traditional storytelling.

For the longer films, we wanted to work within the tradition of tudor folktales – themes such as overcoming nature, the afterlife, and bawdy tales. For these, we worked much more in our usual format: writing story bones and then workshopping/devising with our storytellers (see this blog on our devising technique). These stories were never completely fixed, with the exact telling changing with each filmed take. This led to a really interesting editing process where we stitched together a final version from multiple takes, preserving some sense of the spontaneity of our live performances.

Story #1: Foxgloves

We couldn’t begin to think about telling Tudor folklore without considering Reynard the Fox! In fact, Reynard is thought to be explicitly featured in Ashmole 1504, as the fox dressed as a bishop and preaching to a flock of birds (one of whom presumably will become his dinner!). But when we started this project in the spring of 2021, the Bodleian Library had just released Anne Louise Avery’s stunning retelling of the Roman de Reynard as part of the North Sea Crossings exhibition. So despite being an absolute stalwart of contemporary folklore, we wanted to steer clear of well known Reynard stories. But there were still so many gorgeous foxes in the manuscript that it seemed such a shame not to share, so we were delighted to spot Digitalis Purpurea – more commonly known as a foxglove!

Anyone who follows us knows we love participating in #FolkloreThursday on Twitter. This is a fantastic place to learn all sorts of new stories from all around the world. The etymology of Foxgloves had been shared during one session and was recalled when we spotted the plant in the manuscript. The idea of the fox delicately placing the dainty thimble like flowers on their paws to ensure the hens didn’t hear him coming captured our imagination, and so Foxgloves was born with some help from our in-house wordsmith, Andrew. In fact, this was the first etymology we finished so it was used for all our early camera tests!

David Denyer’s cheeky score perfectly accentuated Howard Horner’s melodious voice, and we think you’ll agree the final thing is simply captivating! It was written by Andrew Hulse.

Story #2: Belladonna

Belladonna was the last short written and probably the hardest. With every etymology we wanted to present the viewer with that satisfying ‘oh’ moment where through the story, you realise what the root(s) of the word is. That root is perhaps more obvious with Foxglove and Swan Song (the answer is in the name after all!) but Belladonna has an extra level of subtlety for being a loan-phrase from Italian and for having a very common alternate name in Deadly Nightshade. Even more interestingly, the Linnaean classification for Belladonna is Atropa Belladonna, which has a further etymological flourish: Atropa (the root for the drug Atropine) is linked to Atropos, one of the three Fates in Greek Mythology – the one who cut the thread of life!

In addition to this fascinating chain of etymologies, Belladonna allowed us to have some cinematographical fun too. Finding swans and foxes in the wild, while hardly impossible, was beyond the scope of our filming days (to say nothing of how difficult wildlife videography can be!), but we had storytellers and macro lenses. The core of the belladonna story is the eye, and so eyes fill much of the footage, sometimes at the expense of all else which is quite powerful in a storytelling video where the spoken word (and the mouth speaking them) has such power.

Belladonna is told by Louise Farnall and the hauntingly beautiful score is by David Denyer. It was written by Andrew Hulse.

Story #3: Swan Song

This film was inspired almost entirely by a single image in the manuscript, an illustration we quickly dubbed ‘angry swan’ – watch the video and you’ll understand why!

We have a local family of swans, and while we can attest that they are angry from time to time, they’re also beautiful, gliding along the canals, barely even rippling the water. It was this latter trait that we wanted to highlight with Swan Song. This is probably the most commonly used word/phrase among the three we chose, with an etymology that’s explained fairly clearly through its meaning. The concept of a swan song has been critiqued for millennia, since the 1st Century with Pliny the Elder at least. This boils down to the accusation that swans make no noise throughout their life except one final song – but again we can attest that they do a lot of hissing!

Despite these zoological debates, the idea was a staple of the Medieval and Ancient World. It appears in Aesop’s Fables, a work that repeats so heavily throughout Western literary traditions that it’s little surprise the swan song etymology is so well known. You can also see it in works by Aeschylus, Aristotle (by which time it was already proverbial), Ovid, Chaucer, Leonardo Da Vinci, Shakespeare and many more.

In our research, we did find one particularly ridiculous anecdote: Zoologist D.G. Elliot in the 19th Century – doing what 19th Century zoologists did best – shot a tundra swan and swore he heard a musical sound of trumpets as it descended through the air. This sounds like a very different sort of interaction of biology and gunshot wound than the literary writers were dealing with.

With Swan Song, we also saw a chance to use a lot more of the manuscript in our film (there are plenty of adorable small frogs). This allowed us to make our most complex collage – the swan gliding across a pond – which used a whole range of elements from the manuscript. The frogs and birds can be found lurking in the corners of the bestiary pages, the plants are cropped and layered to create a busy pondside, and the water is from the vista of a ship upon the sea. All credit for this wonderful animation must go to Hayley (as with all the others as well).

Swan Song is told by Will Mead, with (trumpet-free) music by David Denyer, and is written by Andrew Hulse.

Story #4: The Woodsman and the Wishes

The Woodsman and the Wishes is loosely based on the classic folklore construct of the Foolish Wishes (first recorded under the name Les Souhaits Ridicules in French in the 17th Century by Charles Perrault – though he recognised its much older origin). Really there’s no one better placed to tell you about the story than its storyteller, Howard Horner. He says:

When looking at the manuscript, I was obviously impressed with the beautiful depictions of flowers, trees, and animals – all wonderfully detailed and creative. But I was really taken by the small depiction of a sausage on a grill. We already weren’t sure of the purpose of the manuscript, this fascinating but slightly odd collection of illustrations, and to me this small sausage on a grill was the epitome of this peculiarity. That an artist hundreds of years ago had taken the time to draw this entertained and entranced me – I knew there must be a story behind this humble sausage.

This feeling also chimed perfectly with why I love storytelling as a medium. It is so fantastically playful – small details can blossom into central features as the story billows and unfurls. Researching stories, I found a trope appearing again and again – foolish wishes. This was the perfect framework for my sausage-based story. A playful story where the mundane everyday is infused with magic, the humble elevated to something that could entertain and entrance. It is, above all, fun. And for me, that is more than enough.

The Woodsman and The Wishes is told by Howard Horner, with original music by David Denyer.

Story #5: The Beast of the Bounds

The Beast of the Bounds is probably the story that went through the most iterations. At the beginning of the project, Hayley and Andrew wrote story-bones for four stories (quick reminder, story bones are the five bullet-points that explain the fundamental plot beats of a story; from these we have a basis to begin devising and live-composing). We asked our storytellers to choose which story resonated with them most or come up with one of their own. From our original story-bones, the Beast of the Bounds was the only one that made it to filming.

The story is inspired by the fantastic selection of dogs in Ashmole 1504 and the wealth of dogs in folklore. Their most common appearance is as the black dog; almost every county in England has its own – the black shuck, the grim, padfoot, Gurt Dog, Le Tchan de Bouôlé (yes, you’ll recognise some inspiration for Harry Potter in there). They are almost always linked to ghosts, death, and most interestingly crossroads. Eventually we landed on the Barghest, which won out over all the other names for its cool etymology: a burg (town) ghost.

At the same time, we wanted to pay homage to another staple of folklore: Jack the lad. Jack is the go-to folklore hero. Need a main character? Call them Jack (…and the beanstalk…and Jill). We couldn’t do a folklore project without him.

The Beast of the Bounds is told by Louise Farnall, with original music by David Denyer.

Story #5: Orsa in the Forest

Orsa in the Forest is the last of our longer films. Like The Woodsman and the Wishes, this story began life as something else altogether. Here’s storyteller Will Mead’s explanation:

Orsa’s story originated, rather unusually, from a game of Dungeons and Dragons. I had found myself drawn to the Druid class (a spell caster who could shape shift into an animal form at will) and began to write a backstory about a young adult with a strong connection to nature and the wildlife around them. I needed a reason for this character to be cast out of their community, which became an act of violence against another member over the murder of a beloved wolf and soon (without yet realising) Orsa’s story was born.

A few weeks later I began work on a story for the Needle’s Art Project and was shown the manuscript Ashmole 1504. I particularly enjoyed the animal illustrations and came across a heartbreaking image of a bear in a muzzle (fol. 031r), bear-baiting being a popular sport amongst the Tudors. The anger in the bear’s face reminded me of my recent character’s backstory and I decided that would be the basis of my contribution to the project.

Naturally the wolves of the original story became bears and as part of the devising process we developed a shared lexicon we could use to describe settings, items and action. This set of phrases became useful as I could freely thread them throughout the story as I improvised it on the day of shooting, the result being Orsa’s tragic tale.

Orsa in the Forest is told by Will Mead, with original music by David Denyer.