“He took the lyre upon his left arm and tried each string in turn with the key, so that at his touch it sounded awesomely. And Phoebus Apollo laughed for joy; for the sweet throb of the marvellous music went to his heart, and a soft longing took hold on his soul as he listened. Then the son of Maia, harping sweetly upon his lyre, took courage and stood at the left hand of Phoebus Apollo; and soon, while he played shrilly on his lyre, he lifted up his voice and sang, and lovely was the sound of his voice that followed. He sang the story of the deathless gods and of the dark earth”

Hesiod, 4th Hymn to Hermes

This week we present a guest blog by David Denyer, our resident composer.

The idea of using music with performance is as old as the idea of performance itself. In fact, the word “orchestra” comes from the Latin orchēstra, which itself came from the ancient greek ὀρχήστρα, refering to the space in front of a stage where a chorus would dance and sing. While we have many text sources for the books, plays, stories and poems of old, with music, it’s a different story. The further back in time we go, the notation we have becomes less reliable and understood; trying to understand music’s role, especially on an emotional and dramatic level, in these early forms of storytelling can be difficult.

Notated music, as we understand it, hasn’t existed for long. The current western notation system has its roots in the notations of plainsong chant as early as the 9th century. But the problem with this notation is that it only shows the directions that simple tunes could go – up, down, or stay on the same note – it didn’t say exactly how far up, or how far down, or for how long to stay on that note. It was therefore only really useful for people who already knew how the songs went – and we don’t. Many of these early notations can be interpreted in many different ways and we’re not really sure if the way we sing them now is close to how they were sung at the time. This notation was also only used for religious chant – when it comes to instrumental or secular music, we really have nothing concrete to rely on.

Before this, in mediaeval Europe, we have no recorded pieces of music, and very little information on how any of the music sounded or felt. However, if we go further back, to Ancient Greece, we find another form of musical notation, one used between the 6th century BC and the 4th century AD. Similar to the mediaeval Gregorian chant, this tended to be used for singing texts – a series of symbols above text written in ancient Greek would dictate where that syllable would be placed in the musical scale or mode. Sadly, very few examples of ancient Greek musical notation exist which makes a complete understanding of its practical workings difficult. Like the Gregorian chant notation, it doesn’t tell us much about rhythms or tempo either, only melodics. Unlike Western notation, which is built around octaves (sequences of 7 notes), ancient Greek music was built around tetrachords (sequences of 4 notes), and where Western music thinks about scales going up from the lowest note – ancient Greek music thought about tetrachords going down from their highest note. The intervals they used were also different – the smallest interval we have in Western music is the semitone – but Greek music sometimes used quartertones, which are half the distance of semitones. This makes a lot of reconstructed ancient Greek music sound very unusual to us as a modern audience – and it’s difficult for us to appreciate the emotional or dramatic emphasis that these songs or pieces would have presented to their audiences.

In Politics, Aristotle writes:

“But melodies themselves do contain imitations of character. This is perfectly clear, for the harmoniai have quite distinct natures from one another, so that those who hear them are differently affected and do not respond in the same way to each. To some, such as the one called Mixolydian, they respond with more grief and anxiety, to others, such as the relaxed harmoniai, with more mellowness of mind, and to one another with a special degree of moderation and firmness, Dorian being apparently the only one of the harmoniai to have this effect, while Phrygian creates ecstatic excitement.”

Andrew Barker, Greek Musical Writings

It’s hard to see how the melodic characters of the ancient Greek Phrygian modes might create ‘ecstatic excitement’, but the concept of modality and tonality having distinct ‘characters’ from one another is of course very familiar to us. A modern Phrygian mode is very dark and sinister, while a Dorian mode is transcendent but wholesome and the Lydian mode very optimistic. The social conditioning that originally gave these modes their ‘character’ is long gone, and new social conditioning has emerged to replace it – the music that made the ancient Greeks feel a certain way, now makes modern humans feel a very different way.

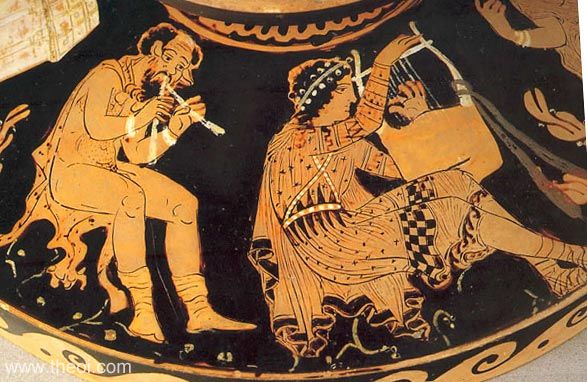

When it comes to modern renditions of classical Greek storytelling, this becomes a challenge. We no longer play the instruments that were once played; we don’t even know the rhythms that were once used and we don’t respond to these modes in the same way that the ancient Greeks did. If we want audiences to see modern interpretations of classical storytelling as anything other than experimental archaeology, we have to try something different. Given that, in Helicon Storytelling, we don’t deliver the lines in ancient Greek, it would be strange to try to recreate the musical languages of the past – so a modern musical language has to be used instead.

But the idea of a ‘modern musical language’ also has problems. Does that mean electric guitars? Synthesisers? Saxophones? That doesn’t seem right either. Ultimately, it really has to tie into the aims of storytelling as a type of performance – but specifically storytelling with a focus on the ancient past. Even in antiquity, these stories carried the idea of ancientness, of oldness, of things having happened in an even-more-distant past. The solution is to find a modern way of telling stories – and of accompanying those stories – that carries an ‘air of ancientness’ that is relevant to us – in the same ways that the ‘air of ancientness’ was relevant to the Ancient Greeks. For that reason, we turned to folk and world music, a genre itself heavy with tradition and a history of aural transmission.

Folk music feels as though it’s been passed from generation to generation, adapted each time, but carrying some fundamental heart that goes back through the ages. ‘Authentic’ in the truest sense – authentic to each individual performer, and each individual generation. The fact that it tends not to be written down makes it easier for these tunes to be adapted and to change and to become individualised for each performance – much in the same ways that storytelling traditions of old would have been individualised. It made the most sense to borrow musical styles and idioms from a world that is the closest thing we have to bardic performance in the contemporary musical sphere. Our approach, then, was ‘authentic’ to some of the methods and approaches to music and storytelling of ancient Greece – while aesthetically being very true to our contemporary audience, drawing from the closest parallels that we have.

When it comes to performing in front of humans, the end goal has to be accessible and appreciable by those humans. No amount of preciousness in the accuracy of the dramatic material would make the work more accessible. To deliver the lines in ancient Greek would be absurdly alienating, and so to try to copy music of ancient Greece, with lyres, psalteries and pan flutes – would also be absurd. The best we can do is to try to recreate the feelings that an ancient audience might have had – mythic, transcendent, a feeling of stories having been carried by generations upon generations of people, of being adapted, altered, improvised, individualised, but delivering a central core that goes all the way back to the creation of the world itself. A childish wonderment, of transformations and machinations of gods, men, mice and frogs, of miracles and godly powers acting in indescribable ways. If we could truly spark the imaginations of audiences, then our storytelling would be as authentic, and as true to its ancient origins, as it could possibly be.